|

| https://unsplash.com/photos/eA32JIBsSu8 |

The Dust Bowl. A decade of repeated drought events. Poor soil management. Non-existent crop rotation. The ripping up of sod on a scale unmatched. We simply asked more than the land could give, year after year, and the land lashed out. And recent research has shown that current elevated carbon dioxide levels make an occurrence like the Dust Bowl twice as likely.

Deforestation. The World Bank estimates that roughly 500,000 square miles of forest were lost between 1990 and 2016. For comparison, that's about 90% the size of Alaska. Wow. And harvested trees release stored carbon into the atmosphere, exacerbating the current runaway atmospheric carbon content issue.

Rising sea levels. According to satellite data, sea level in 2014 was 2.6 inches above the 1993 average, the earliest comprehensive satellite data that we have. Yes, 2.6 inches seems small to me, too. So let's examine that in further detail.

Picture an acre. Have it in your mind? One acre is 43,560 square feet. Yes, I have that number memorized from my days in engineering school. Still, it seems abstract, so let's zoom in.

For those of you who live in suburban America, your house likely sits on one-fifth of an acre, give or take. So five of the plots of land that your house sits on make an acre. Good. Now rainfall, in both hydrology and agriculture, is often measured in acre-feet. One acre-foot refers to one foot of water depth that covers an entire acre.

Seawater accounts for approximately 139 million square miles of the earth's surface. There are 640 acres in a square mile, so that makes for 88.96 billion acres of seawater on the earth's surface. A rise of 2.6 inches across this surface therefore equates to 19.27 billion acre-feet of water. Perhaps that number sounds a bit larger than 2.6 inches and more accurately conveys the scale of what is happening.

Furthermore, as the planet continues to warm, sea levels will continue to rise due to thermal expansion of the ocean itself. And because of climate change, glaciers and polar ice caps continue to melt at an increasing rate, driving levels even higher. This is bad news for communities in low-lying areas, including the Seychelles Islands, the Chesapeake Bay region of Virginia and Maryland, the Netherlands, and countless others. And we spend billions of dollars desperately fighting to keep the water at bay rather than changing our energy needs and usage.

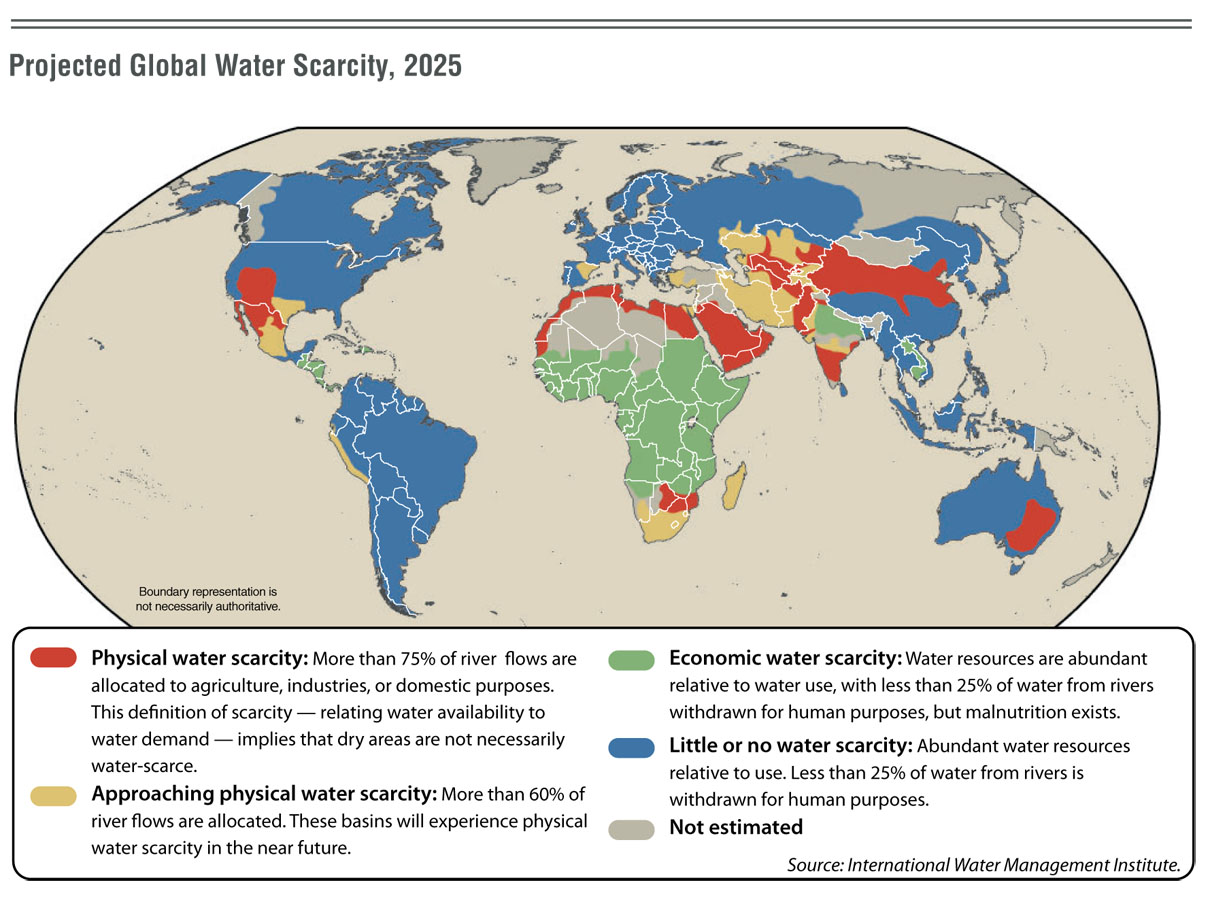

Water scarcity. Growing populations, increasing urbanization, and greater industrial use of water further stress the availability of this critical resource. While total water content on the planet remains relatively stable over time, usable and accessible water does not. As we draw more water out of aquifers and reservoirs and drink it, flush it, irrigate fields with it and pump it full of nitrogen, and send it on down the river to the ocean, it ultimately becomes brackish seawater. We can't use saline water for much, short of costly desalination. And we are sending water to the ocean at a faster rate than it is replenished over the landscape as freshwater via precipitation.

|

| https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/world_maps/water_scarcity_2025.jpg |

And before you respond that it's rained quite a bit recently where you live, or conversely, that your region is in a severe drought, let me stress that the overall effect of climate change is to produce greater extremes. Lengthier droughts, stronger hurricanes, more intense rainfall and storms, a prolonged wildfire season, etc. And all of this can be tied directly back to human activity.

The above examples are just a sampling of the current state of the Earth's climate. It's a complex problem. A wicked problem, in fact. We seek economic growth, greater access to food, shelter, and water for all, improved quality of life; all good things. But we are finding it difficult to reconcile the manner in which we go about it with negative long-term effects on the Earth. Let's be clear, though; the Earth will be fine. It is our own position that we make more precarious as we march ever forward in the pursuit of growth and advancement. We scar the world, time and again, and continue to ask it for more. History has shown us that there comes a time when the Earth lashes out.