|

| https://unsplash.com/photos/6WrKKQcEnXk |

What follows is a flash fiction story that I wrote for a project called "Stories of the Nature of Cities," with a vision of what cities will look like in the year 2099. The focus of the project is, of course, on transdisciplinary thinking and efforts to make for a more connected and greener city. More about the project can be found on The Nature of Cities website.

Whether the global pandemic of 2020 casts any doubt on the viability of cities is undoubtedly a concern, but it seems that that is where further innovation can come into play to make cities feel safe to the masses and allow them to continue to thrive. Density, previously a key selling point of cities, is naturally considered less than ideal in the midst of a pandemic. But, one could argue, perhaps it is also this same proximity that has allowed us to build the institutions that we have that have led to the relatively quick rollout of a vaccine.

Cities are, without a doubt, hubs of innovation. But in the following flash fiction story, I focus on a simpler version of a city. One that is smaller, and based on communal cooperation and mutual care and trust. A community and society that promotes the common good, while maintaining concern for the individual, is one we can all get behind. The fictional story that follows is one that I feel epitomizes the type and quality of life we aim to promote here at Deliberately Aimless. Welcome to the notion of SimpliCity, otherwise known as Peace River.

→Peace River

Diana watched from under her visor as the green leaves fluttered in the breeze above her. She took a spade from the wheelbarrow next to her, relishing the feeling of its wooden handle in her grasp. This tool allowed her to cultivate both her own food as well as an intimate relationship with the natural world, an experience she realized she shouldn’t take for granted. It was only a short while ago that people had little contact with nature; a sizeable portion still didn’t. In humanity’s quest to eliminate hardship and effort, it had unwittingly removed purpose from life. As Diana saw it, many in the mid-century period became shells of their former selves, having no physical concerns, and thereby no connection to their bodies, to nature, to each other.

But things were changing. On the eve of the 22nd century, there was a movement by a significant portion of the population to re-establish the small town, to leave behind the concrete jungle, the overcrowding, and the desultory life. Many would choose to stay in the still-growing cities, for the convenience; others desired something more: to know Mother Nature.

With this aim in mind, Diana had moved to Peace River, high on the Canadian prairie, a year ago. When she arrived, she hadn’t witnessed a utopia in action; pursuit of utopia had made the megacities what they were. Neither were these remote communities communist. They still operated under capitalist principles, but not the capitalism that you and I know. Currency existed and people held occupations, sure, but interest was not earned on loans and wealth was not created simply by manipulating markets. The towns operated under the not so radical idea put forth by Solomon in Proverbs, that “dishonest money dwindles away, but he who gathers money little by little makes it grow.” In fact, this described much of the outlook of how the town operated as a whole, not just as pertains to commerce. Nature, too, was something to be used little by little, as needed, but not without tender care.

Diana had found employment as a journalist, covering the goings-on in the town of about 7,000. She enjoyed riding her bicycle to her appointments, the global warming of the past century having made the winters of the northern prairies more tolerable. Most of the town’s residents commuted by bicycle, much as the Dutch had used to do before rising seas had forced many of their number into the megacities. Life moved at a slower pace in Peace River, and the residents subsequently found themselves without regular need of automobiles. A train line ran once daily to Edmonton, and a city-subsidized rental facility allowed residents to rent autonomous cars on an as-needed basis.

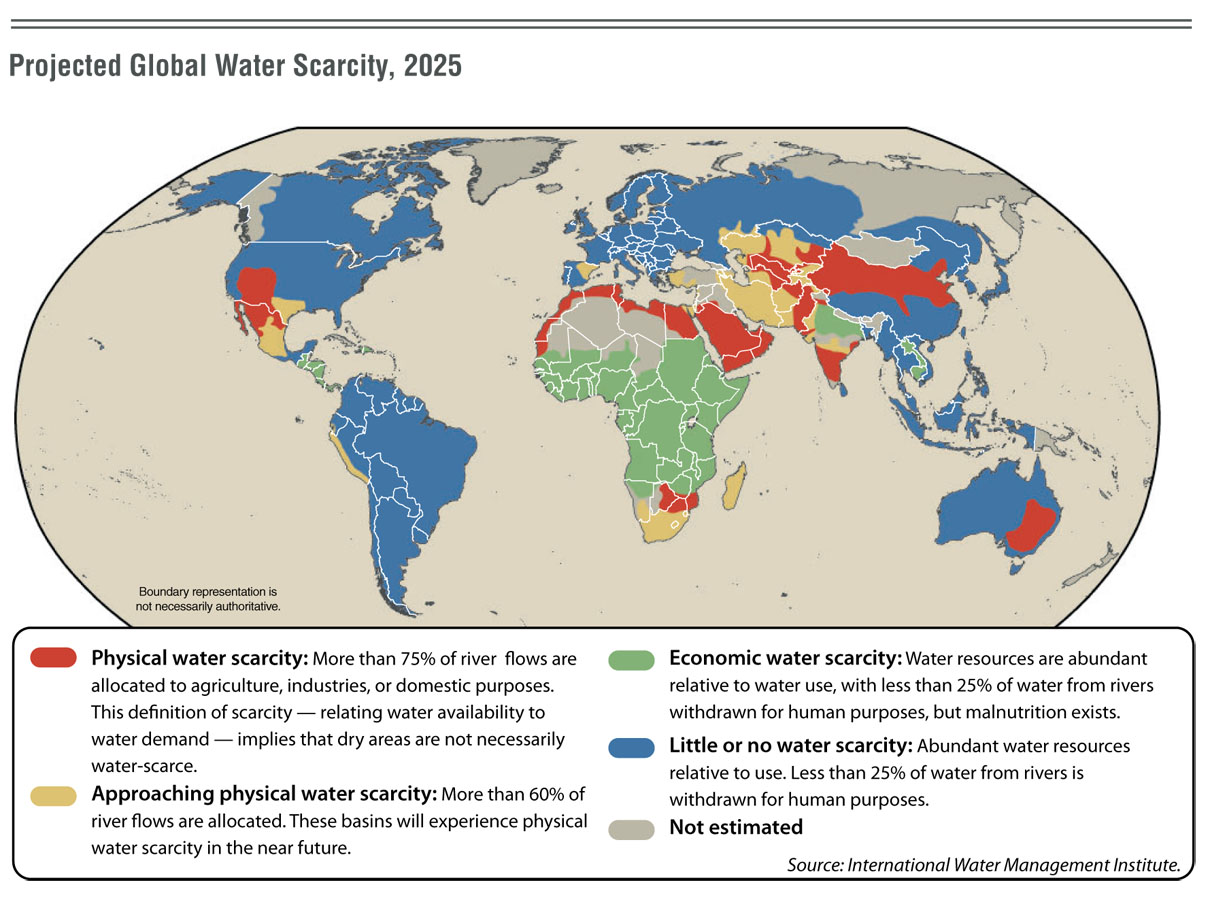

Digging the nose of the spade into the soil, Diana upturned a small amount and deposited the potato tuber, covering it back over. She trenched a line about thirty feet long, and continued planting about every twelve inches. Finishing, she tossed the spade into the wheelbarrow and pumped some water from the nearby well into her bottle, savoring the fresh taste as she drank it down. Northern Alberta had outlawed the use of pesticides nearly eighty years before, and all cities had moved to grey water systems, to reduce the amount of waste entering streams. In that time, the groundwater tables had begun to recover, in terms of both quality and quantity. The installation of bio-swales and permeable pavement throughout town had also helped with the infiltration of rainwater and snowmelt, intercepting portions of it before it could runoff into the river, where it would become “lost” due to salinity when it entered the sea, until such time that it precipitated over land again.

Which reminded her that she needed to meet Tom back at the house to have him check the pressure in her front room radiator. She walked round to the front just as he was riding up. He leaned his bicycle against her wire fence, and she led him inside. A socialite, Tom explained as he set to work. “I see you have the newer units with the gridded folds to maximize surface area. That helps with efficiency. So what seems to be the problem?”

“It’s been emitting a high-pitched sound when it runs. I’m worried about the pressure since we run recycled water through them these days.”

“Understandable, don’t want to have that sort of mess to clean up. Again, it’s more efficient to run re-used water through, but I understand the concern.” Tom made quick work of it, replacing a fitting and O-ring, and was soon on his way.

“Thanks, what do I owe you?” Diana asked as he headed down the steps.

“Nothing, it’s part of your community fees. The city, which is to say the people, take responsibility for all municipal water services, even into the house. Have a good evening.”